Photograph of a massive protest in Greece by Kotsolis, licensed under Creative Commons 3.0 Share and Share Alike. These citizens are protesting a 2011 decision by the Greek government to agree to the International Monetary Fund’s demands that they cut public spending and raise taxes.

The eyes of the world have been riveted on Greece in recent days. Some might struggle to understand why. After all, how does what happens in another country effect us?

However, what is happening in Greece right now is very, very important to the whole world. Why?

Two reasons:

1) In this globalized world of virtual currency exchange, all economies are interconnected.

Particularly important is the habit of “buying debt” – when someone owes you money, essentially, you can sell that debt to someone else. In the exchange, the buyer will receive the money the person pays on the debt, plus interest; you will receive money up-front from the buyer instead of waiting for the debt to be paid back to you.

Interestingly, debt is sometimes sold for much less than the original value of what a person owed. This has led to The Rolling Jubilee’s innovative approach to tax relief, whereby they use donations to purchase “distressed debt” – that is, debt that the debtor is not able to currently pay – and forgive it. Distressed debt is often sold much for much less than the original price of the loan by creditors who want to get some money from the debt instead of none.

So when the Great Recession was spawned in the United States, for example, that hit everyone – because many other world economies (including Greece) had bought our debt, such as subprime mortgages, believing that they would profit in the long run. So when American banks and individuals declared that they were too broke to ever pay off their debts, buyers all over the world suffered – and since many of those buyers were also investors, stock markets all over the world suffered too.

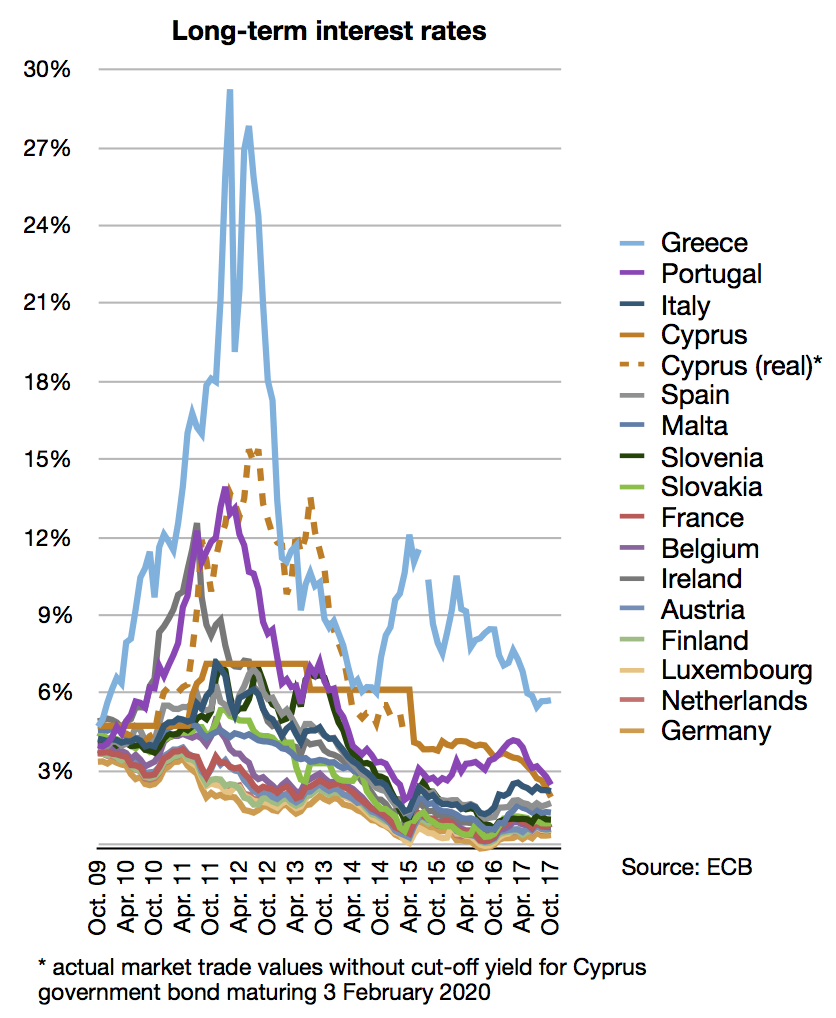

This graph of interest rates across the Eurozone created by Spitzl. Licensed under Creative Commons 3.0 Share and Share Alike.

Everyone who has bought pieces of Greek’s national debt – including most of Europe – now faces the prospect of having it not paid back. This means that people will only lend to Greece if they hope to gain something from it by charging astronomically high interest rates, which worsens the country’s overall financial situation.

This, in turn, is discouraging people from investing in markets that may be negatively effected by Greece’s failing to pay back the debts from which investors were expecting money. The cycle continues.

2) Greece is being upheld – not always justifiably – as a model of what happens when states provide generous social services to their peoples.

In the reasoning of fiscal conservatives, Greece represents the logical conclusion of the path that all “welfare states” are on – unsustainable spending leading to certain collapse.

This is going to make voters and politicians alike around the world skittish about anything that involves government spending; including investing in education, socializing medicine, etc.. And, in some cases, they may be right.

So it is very important to understand what actually happened in Greece; so that we might avoid it happening here, and so that we may not suffer from acting on incorrect or incomplete understandings of the situation.

So what actually did happen in Greece? It turns out to be quite a bit more complicated than simply “socialism doesn’t work.” Here’s what I found in a review of scholarly and popular articles on the subject:

Was socialism/the welfare state what killed Greece’s banks?

Yes and no. While it was government spending on public sector employees and services rendered to citizens that ran up Greece’s debt, that was far from the only thing that was going on.

There was also, for example, a rather horrifying lack of tax revenue. As liberals in the U.S. are quick to point out, you cannot finance social programs without tax revenue.

On paper, Greece’s tax rates were fairly typical for a European state. However, in practice, what was actually being paid was much less than any European state except for Ireland.

It turns out that Greece had a deep-seated culture of tax dodging. This may date back to feudal times, when favors between politicians and people were traded as a matter of understanding; the idea of having to pay for these services in addition to simply supporting your politician was alien and somewhat offensive.

So the people of Greece didn’t pay for the services they received from the government. An estimated $20 billion per year or more that should have been paid in taxes to keep the system functioning was not – which may sound modest to a U.S. reader, until you consider that with Greece’s meager population of 11 million, that’s at least $2,000 per person, per year, of what was essentially taking advantage of government services without paying for them.

No wonder the Greek government was forced to borrow so much from other countries.

Although the tax dodging problem has been called “the most obvious” cause of the Greek debt crisis, there were other problems, too. Transparency International, for example, rated the Greek government as the most corrupt in southern Europe – which doubtless translated to even more bureaucratic expenses that had nothing to do with actually providing services to the people.

Indeed, one study found that among OECD nations, Greece paid far more for the services it provided to its people, and yet “there was no evidence that they were greater in quality or quantity than those of other OECD nations.”

This may be partially explained by another component of Greece’s age-old culture of paying for services with loyalty: in addition to endemic tax dodging, it was quite standard for Greek politicians to create cushy government jobs and award them to their supporters, irrespective of whether the jobs were actually necessary.

In other words, the money Greece was spending “on social services” was not actually going to social services. It was going to pay public sector employees whose jobs often had, in reality, more to do with rewarding political loyalty than actually providing goods and services.

The last factor commonly cited as contributing to Greece’s decline was an overly complex system of laws; this system, perhaps intentionally, produced tremendous bureaucratic overhead and poor compliance. There were so many legal loopholes and bylines that evading the law was easy when it came to budgeting; and enforcing it was tremendously expensive.

So, was Greece’s problem that it provided too many social services to its citizens?

Ultimately, no.

While continuing to run its bloated and corrupt system on borrowed money is what led to Greece’s decline, as stated above, much of that money did not actually go to providing, say, healthcare or education to its citizens.

Instead, much of the money went into the pockets of private individuals through cushy government paychecks.

In other words, Greece’s system would have been much more sustainable if its public spending had actually been oriented towards providing valuable services to its citizens.

In addition to becoming a leaner, meaner, more efficient service-giving machine, Greece could have avoided many of these problems by simply paying its taxes.

Most Americans would probably jump at the chance to pay just $2,000 per year in exchange for all the healthcare they could possibly need, Greeks simply didn’t feel the need to pay taxes on their income. And they expected the social services to continue working anyway.

So if Greece had provided the same level of social services to its citizens without the corruption and tax evasion, they might have had an entirely different outcome.

So what happens now?

That is the question of the hour. Greece’s endemic tax evasion and inefficient spending has left all of Europe between a rock and a hard place.

The first instinct when seeking to reduce debt created by over-spending is to demand less spending; but cutting social services now could run the Greek economy further into the ground by resulting in Greek people having less money to spend on goods and services. If Greek consumers stop buying, Greek businesses will tank; and so, too, will tax revenues.

And yet, if government spending continues as it is, it could be perceived as having no consequences for Greece’s rampant corruption and tax evasion. This could encourage the bad behavior to continue.

Last week, Greece’s leadership encouraged its citizens to vote “no” on accepting the European Union’s offer to forgive some of Greece’s debt in exchange for Greece committing to pay the rest and taking certain measures to ensure that happened.

The Greek people did as they were urged, and essentially told Europe that they are too poor to ever pay off their debt.

This photograph of a classical Greek statue of Athena, goddess of wisdom, has been generously released into the public domain by Jastrow.

Many economists believe that this was yet another bad move on the part of Greece’s government; by defaulting on their existing debt, they have essentially precluded the possibility of anyone else lending money to them, or investing in their obviously-distressed stock market.

What will happen to the Greek people now is uncertain. It will be a long, hard road ahead for a country which has been spent into oblivion due to a confluence of factors which are more cultural than mathematical.

I wish the Greek people all the best in this difficult time. It is, arguably, not the fault of any one individual; likely none of the many moving parts involved knew what they were setting their country up for as a whole.

And I send this caution to citizens of all countries who wish to see their national debt reduced:

Pay your f*cking taxes.

Maybe even consider raising them.